All those writers buried away in self isolation and trying to describe what we are all experiencing could do worse than turn to Thomas Dekker’s ‘A Wonderful Year’, his account of living through the plague in 1603.

All those writers buried away in self isolation and trying to describe what we are all experiencing could do worse than turn to Thomas Dekker’s ‘A Wonderful Year’, his account of living through the plague in 1603.

Dekker was a young playwright around town in Shakespearean London, very much on the make, and constantly in and out of trouble and prison for debt.

.

Come the plague in 1603, and all the theatres closed – lockdown was always immediate if deaths from the disease reached just 30 a week – so Dekker turned his hand to pamphleteering to make ends meet.

The challenge was to attract a readership who might not want to be reminded of what they were only just escaping when the pamphlet came out. Dekker’s answer was to try to make much of it as funny as he could: ‘If you read, you may happily laugh; tis my desire you should, because mirth is wholesome against the Plague.’

There is a black humour to his accounts of the lengths to which Londoners would go to ward off the foul-smelling odours thought to bring the disease with them. He describes how people would walk along with rosemary and herbs stuffed up their ears and nostrils, ‘so they looked like pigs being served up for Christmas’; rosemary became the hand sanitiser of its day, with the price Dekker mordantly notes, rising astronomically from ‘12 pence an armful to six shillings a handful’.

Dekker is best known for The Shoemaker’s Holiday, a boisterous, rowdy comedy of London life, and he manages to get plenty of choice anecdotes in here. The finest is that of the cobbler’s wife, who stricken with all the symptoms of the plague and on her deathbed, calls her husband and her neighbours to her, to confess before she dies that she has had many affairs and treated him wrongly.

Dekker is best known for The Shoemaker’s Holiday, a boisterous, rowdy comedy of London life, and he manages to get plenty of choice anecdotes in here. The finest is that of the cobbler’s wife, who stricken with all the symptoms of the plague and on her deathbed, calls her husband and her neighbours to her, to confess before she dies that she has had many affairs and treated him wrongly.

This news is greeted with the mixture of surprise and respect appropriate to the context, as the neighbours urge the cobbler to be philosophical in the face of his wife’s approaching death and not take his cuckold’s horns too seriously. A high moral tone is taken. At which point, of course, she unexpectedly recovers and then has to face both husband and, far worse, her neighbours’ wives, in the long months afterwards:

‘They came with nails sharpened like cats, and tongues forkedly cut like the stings of adders, first to scratch out her false Cressida’s eyes, and then (which was worse) to worry her to death with scolding.’

But along with the jokes, Dekker gives one of the most vivid eyewitness accounts of what it was like to live through a London plague at that time. This was not one of the great plague years of the 14th century or its last hurrah in 1665. But his description of London during a year in which 1000 Londoners were dying a week (30,000 all told) still makes for sobering reading.

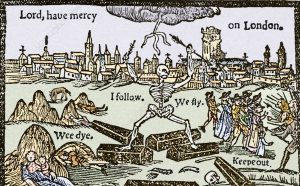

He imagines London as a vast charnel house, hung with lamps and scattered with the bones of the dead:

‘For he that durst (in the dead hour of gloomy midnight) have been so valiant, as to have walked through the still and melancholy streets, what think you should have been his music? Surely the loud groans of raving sick men; the struggling pangs of souls departing. In every house grief striking up an alarm: servants crying out for masters; wives for husbands, parents for children, children for their mothers… And to make this dismal consort more full, round about him bells heavily tolling in one place, and ringing out in another. The dreadfulness of such an hour is unutterable.’

Dekker is humane, funny and at times angry, lashing out at sextons who profited from the fee they received for burying each corpse. Nor does he have much time for doctors, many of whom fled and whose expensive remedies did less good to alleviate the suffering, in Dekker’s opinion, than a good pint of ale and some nutmeg. He also has a profound empathy for London as a city itself: ‘ In this pitiful (or rather pitiless) perplexity stood London, forsaken like a lover, forlorn like a widow, and disarmed of all comfort.’

Is there something we can take too from his antagonistic attitude to death? He had begun this same pamphlet by lambasting Death for killing Elizabeth I, who had died earlier that year in March before the plague arrived (‘On Thursday it was treason to cry “God save King James” and on Friday high treason not to cry so.’)

Now he pictures death as a tyrant storming the city, pitching his tents (‘being nothing but a heap of winding sheets tacked together’) in the suburbs: the plague as ‘Muster-master and Marshall of the field’, with his acolytes being professional mourners, ‘merry’ sextons, hungry coffin-sellers, pall-bearers, and ‘nasty’ gravediggers. ‘Death, like a thief, sets upon men in the highway, dogs them into their own houses, breaks into their bedchambers by night, assaults them by day, and yet no law can take hold of him.’

Meanwhile a great army of Londoners are sent packing by his arrival, ‘so that within a short time, there was not a good horse in Smithfield, nor a coach to be set eyes on’; fleeing to the country where they are met with suspicion and resistance (one country innkeeper barricading himself into his cellar so he didn’t have to serve the dangerous newcomers).

For those that remain the future is grim. Private houses ‘look like St Bartholomew’s hospital’ and he has a vision of 3000 of the dead trooping together to their deaths, ‘husbands, wives & children, being led as ordinarily to one grave, as if they had gone to one bed’.

Dekker compares himself to one of those soldiers at the end of an extraordinary battle, who ‘with a kind of sad delight can rehearse the memorable acts of their friends that lie mangled before them’. As an elegy for a terrible year, his pamphlet deserves more than to be buried at the back of the collected works of a little-known playwright.

An online version of Dekker’s A Wonderful Year’ can be seen at http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/yeare.html