Roger Deakin, Wildwood (Hamish Hamilton, £20). Reviewed for the Independent

Greta Hopkinson was a visionary and neglected sculptress, born at the end of the 19th Century but having more in common with the current practice of Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy. She lived in the New Forest that meant so much to Roger Deakin, and chose to work with wood that had fallen naturally into its streams. The water shaped these pieces into unusual twisting forms that brought out the grain in a way that no lathe or chisel could achieve. I knew her as a boy when she was in her seventies and would see her returning from a forage around the holly holms with her arms full of beech or oak, ‘found work’ which she would then shape further, or leave.

I was reminded of her by this extraordinary book by Roger Deakin; his last, as he died shortly after its completion. The original manuscript was many times the length. It has been whorled down to a series of concentric and concise rings around its subject, and the result is some of the finest naturalist writing we have been lucky enough to receive for many years: ‘In the pine top of my work table, the dark knots are boulders standing up in the rivers of grain, sending eddies and ripples spinning downstream, delivering the driftwood thought of a new journey to be taken, through trees.’

At its centre is the oak, chestnut and ash-framed house Deakin re-built with his own hands close to Suffolk common-land – a house familiar from his previous book, Waterlog, and from his Radio 4 series, a house which he informs us with characteristic erudition is eighteen feet wide because that is the average limit of the crossbeams a suitable oak can provide.

At its centre is the oak, chestnut and ash-framed house Deakin re-built with his own hands close to Suffolk common-land – a house familiar from his previous book, Waterlog, and from his Radio 4 series, a house which he informs us with characteristic erudition is eighteen feet wide because that is the average limit of the crossbeams a suitable oak can provide.

An archipelago of ‘writing sheds’ are scattered in the trees around the house, some so hidden by the undergrowth that they resemble moles’ burrows into which Deakin can retreat to sleep as well as write, emerging like the hero of Wind in the Willows to greet a watery and wildwood world. A typical moment occurs when he awakes to find the whole hut rumbling and shaking, before realising that a roe-deer is rubbing herself against a corner of the hut, inches from his pillow.

From the still centre of this Suffolk home, Deakin begins his arboreal odyssey by travelling to the New Forest. As a young student, it was there he had first learnt the patient, close observation of nature which was to become his trademark: he describes a back-lit spider’s web following the same pattern as a tree-trunk, ‘ the radial threads representing the medullary rays of wood, along which a trunk will sometimes split as it dries’.

.

This is naturalist writing in the footsteps of Gilbert White or Geoffrey Grigson – not only in the rigour of its style but as part of a literary tradition comfortable with the interweaving of nature with art, history and a life lived outside the narrow confines of biology. Not for Deakin the completist lists of species pinned to the page like butterflies or moths; each phenomenon of nature is puzzled over, and sometimes left unresolved, more in the spirit of Renaissance enquiry than contemporary dogmatism.

This is naturalist writing in the footsteps of Gilbert White or Geoffrey Grigson – not only in the rigour of its style but as part of a literary tradition comfortable with the interweaving of nature with art, history and a life lived outside the narrow confines of biology. Not for Deakin the completist lists of species pinned to the page like butterflies or moths; each phenomenon of nature is puzzled over, and sometimes left unresolved, more in the spirit of Renaissance enquiry than contemporary dogmatism.

No other writer could make a mountain out of mousetail, the miniature buttercup so small as usually to escape notice, indeed so small as usually to be walked on. Deakin’s patient investigation of its curious propagation with the help of the New Forest ponies – who trample and manure the ground during horse fairs – is a model of lucid investigation.

.

From the New Forest he ventures further – through Devon, the Forest of Dean and abroad to the Pyrennees, Australia and the walnut trees of Kyrgyzstan – before circling back to his ‘Heartwood’ of Suffolk. Just as fallen wood in a forest attracts a host of funghi, bacteria, woodlice and insects, so this journey teams with ideas of startling and protean abundance: from why so many woodland plants should be poisonous to the use of walnut in a Jaguar’s gear knob; why both moths and Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert are so drawn to the light; even a section that harks back to Britain’s pre-lithic ‘wooden age’ when great circular henges made from posts of pine or oak were built, anticipating Stonehenge by several millennia – indeed that monument may only have been built as a later stone complement to an original Woodhenge at the same site. Companions on the journey range widely, from Ruskin, John Nash and William Cobbett – whose hatred of enclosure Deakin shares – to the engaging members of the rival Essex and Suffolk moth societies, each trying to lure the magnificent convolvulus hawk moth across the river Stour that divides them.

Back home in Suffolk from his travels, and the first tree he greets is a tall brooding Devonshire Quarrendon, grown from an apple pip taken from Ted Hughes’ orchard; a reminder of Deakin’s campaign with the Common Ground pressure-group he founded for a greater variety of English apple to be grown in the face of supermarket homogenisation. One particularly unruly variety he approvingly christens ‘Tesco’s Despair’ for its stubborn refusal to grow to a uniform size and shape.

At one point Deakin notices how some insects are drawn to the brightness of a book he is reading, the reflected sunlight luring pearl-bordered fritillaries, dragonflies and damselflies. Many more have settled in these pages, from dark spinach moths to sticklebacks – and Wildwood is also suffused with the soft cooing of wood-pigeons, the lyrical blackcaps and lesser whitethroats, the piping of robins and wrens, chiffchaff and the confident glissando of the chaffinch.

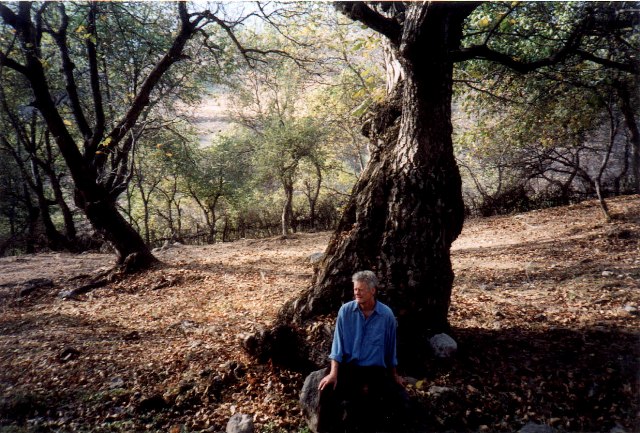

Near the end he describes a pollarded hornbeam near his home, shaped like a church bell into which he can swing himself to read. During a wind, the surrounding wood shelters itself; ‘all you hear.. is a sound with the quality of a shingle seashore not far away’.

Near the end he describes a pollarded hornbeam near his home, shaped like a church bell into which he can swing himself to read. During a wind, the surrounding wood shelters itself; ‘all you hear.. is a sound with the quality of a shingle seashore not far away’.

Such aquatic metaphors abound – the timber frame of the house ‘sits lightly on the sea of shifting Suffolk clay like an upturned boat and rides the earth’s constant movement’ – and might be expected by readers of his previous book Waterlog, which followed an engaging conceit: the idea that like Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer, Deakin could breast his way across England by its pools and wilder inland waters. But while Waterlog won him a devoted following, and one which was extended in his intimate radio series, the writing was not nearly as assured as here.

A man who lived most of his life with a pencil behind his ear, with which to measure his own joinery or to write – for whom a pencil was an ‘intimate, elemental conjunction of graphite and wood, like a grey-marrowed bone’ – Deakin was at ease with nature in a way that only a poacher with very deep pockets can be. It is fitting that his last book should be his masterpiece.

(c) Hugh Thomson 2007

Hi,

I have inherited some postcards and correspondence between Greta Hopkinson and my grandmother, and am interested in finding out more about her. Do you have any tips as to where I could find more material on her?

Thank you,

Have a nice day!