Tequila Sunset’, by Hugh Thomson

published by the Financial Times

Hugh Thomson goes in search of the true tequila experience

.

.

.

.

Tequila used to be a real man’s drink – straight up and raw; the only accompaniment allowed was a pinch of lime and salt. One of PG Wodehouse’s pre-war characters ordered ‘a shot of that Mexican drink that they call – no, I’ve forgotten the name, but it lifts the top of your head off’.

For many years in the States it was considered much like cheap vodka in the UK, a quick way for students to get drunk cheaply. But some astute brand positioning has changed that, along with the advent of the ubiquitous Margarita – to the point where it is almost in danger of becoming effete. On a recent visit, one hotel menu in Cancun offered me a ‘Chocolate Tequila’ which apparently ‘dazzles the tastebuds with 2 ounces of reposado tequila, 1 ounce of crème de cacao and a dash of Hersheys chocolate syrup, stirred and served straight up in a stemmed glass topped with a cherry’. No thank you.

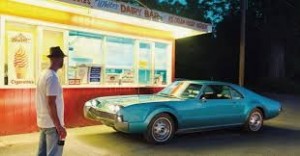

I first travelled through Mexico in the late 1970s when the stirrings of such adulteration were only just beginning. My journey began on the Tex-Mex border where I was buying an American car to take me right through the country, with the naive and youthful hope that I’d be able to sell it further down in Central America.

Finding the right (and cheapest) car in Ciudad Juarez – now the city with the largest crime rate in Mexico, mostly drug-fuelled, but back then merely insalubrious – meant a lot of meetings in bars. The local speciality was the ‘bandera’ or ‘flag’, where the barman would line up three shot glasses of red, white and green for the Mexican colours: sangrita, neat tequila and a lime chaser respectively. The tequila came in cheap plastic bottles and purity left a great deal to be desired – but then it was knocked back so fast no one noticed .

Finding the right (and cheapest) car in Ciudad Juarez – now the city with the largest crime rate in Mexico, mostly drug-fuelled, but back then merely insalubrious – meant a lot of meetings in bars. The local speciality was the ‘bandera’ or ‘flag’, where the barman would line up three shot glasses of red, white and green for the Mexican colours: sangrita, neat tequila and a lime chaser respectively. The tequila came in cheap plastic bottles and purity left a great deal to be desired – but then it was knocked back so fast no one noticed .

It wasn’t until I’d bought the car – a classic Oldsmobile 98 – and driven further south to the state of Jalisco and the eponymous town of Tequila that I began to see the drink treated with anything like the respect it deserved, and by the people who made it. An old man in a liquor store taught me to check that any bottle stated it was ‘pure 100% agave’ and to tell the difference between the tequila of ‘The Valley’ and that of ‘the Highlands’ – that of the Highlands having a more flowery taste and smell. I watched the blue agave plants being harvested, the spiky stems cut off and the heart split open almost like a pineapple. The better distilleries were those that bothered to remove the bitter pith at the centre of the plant before distillation.

.

By the time I got down to Mexico City, I had run up a formidable bar and petrol bill, so found some much needed work at a development bank as a translator and all-round gopher. The boss’s name was Julio. The first day, Julio took me out to lunch and explained the principles behind doing successful business in Mexico. Everyone worked from ten until two. An extended lunch would then go on for hours, sometimes until five in the afternoon, before everybody headed back to the office until eight in the evening.

Lunch was the real work. ‘Our business depends largely on trust,’ said Julio. ‘The idea is that Mexicans can only trust one another when they are so drunk they are almost blind. So in this bank we always drink Tequila Oils before we begin any negotiations.’

.

By now, I prided myself on having drunk tequila most of the ways it came – from classic Margaritas to the dark Conmemorativo that looked more like whisky. I had even sunk to the depths of the abominable Sunrise and all sorts of sugary variations. But I had never heard of a Tequila Oil. It had apparently been named in honour of Mexico’s petroleum boom.

By now, I prided myself on having drunk tequila most of the ways it came – from classic Margaritas to the dark Conmemorativo that looked more like whisky. I had even sunk to the depths of the abominable Sunrise and all sorts of sugary variations. But I had never heard of a Tequila Oil. It had apparently been named in honour of Mexico’s petroleum boom.

Julio gave an order to the waiter. He came back with a double tequila mixed with tomato juice. I didn’t like the look of this (tomatoes belonged with vodka), but it still seemed plausible. Then Julio took a large tablespoon of the habanero chilli sauce that was on the table and ostentatiously mixed it in. Other diners were beginning to watch him. He took a bottle of black Maggi out of his briefcase. I had seen the stuff in European restaurants, a sharp, aromatic version of HP sauce. He stirred enough in to turn the drink black and viscous. It did indeed look like oil.

‘Try this, Hugito. Just as the alcohol hits your stomach, the chilli will as well and blow it back into your brain. It will take your head off.’ And it did.

.

So began a memorable set of serious lunches. Julio and I would turn up at a factory, fence around the issues with the bosses and then go to one of the many wonderful restaurants in the city. We would order dried ants in chocolate, or mole poblano, the great national dish of dried chillies, turkey and chocolate (‘¡Ricísimo!’ the Maître D’ would murmur appreciatively as he took our order). Julio would get out his mixing kit, line up three or four of his Tequila Oils in front of everyone at the table and within half an hour we would all be friends for life, and have a sensibly re-negotiated loan.

Julio had one favourite phrase whenever we finished off a negotiation: ‘Hey,’ he would say, spreading his arms wide and laughing, ‘it’s not my money, after all.’ Which would be a cue for drinks all round.

After a fabulous journey that took me to the wilder shores of Mexico, I finally arrived in Belize, where I planned to sell the car; by now I was drinking more beer than tequila, which had to be imported and was expensive. In the first town I came to, Corozal, I went straight into the local bar to see if I could find a buyer for the car. The barman was called Roach, and was in his fifties, with deep black skin and a grizzled look. I told him about my long journey down from the Texas border. ‘So what do you think – can I sell it?’

Roach looked at me as if I were stupid. ‘Of course. You’ve come to the right place. Everybody in Belize wants an American car. Might even want it myself. Where is it?’

.

But when he saw it, he started to laugh – big, sobbing laughs that rocked his considerable frame. The car was, admittedly, a bit of a mess after its long journey, but nothing that a bucket of water couldn’t put right.

‘I’m sorry, you’ve made one big mistake. This car only has two doors.’

‘So. It’s an Oldsmobile 98, prime condition, with electric windows.’ I demonstrated. ‘It’s only supposed to have two doors.’

.

.

‘Down here,’ said Roach, ‘we want four-door cars. The only one way anybody can afford to have a car is to use it part-time as a taxi. A two-door car is useless as a taxi. And even if anybody wanted your car, they would never sell it on to anybody else. There’s no re-sale value.’ He stressed re-sale value with relish.

I rocked back on my heels. For the first time in my life, I realised the full value and meaning of the term ‘market research’.

It was time for some of Roach’s imported tequila. I showed him how to mix up a makeshift Tequila Oil.

‘That’s a good drink,’ he said approvingly: ‘There are times in a man’s life when he needs more than a beer – and this is clearly one of them.’

.

Hugh Thomson’s Tequila Oil: Getting Lost in Mexico has just been published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.