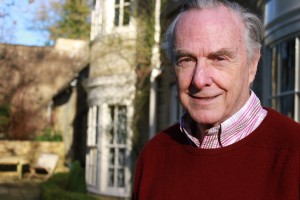

John Hemming is the epitome of a certain sort of English gentleman – courteous, retiring and extremely modest. Now 75, he was the Director of the Royal Geographical Society for over two decades. He has written definitive histories of both the conquest of the Incas and the tribes of the Amazon. But beneath the reserved exterior of this scholarly explorer lies a life of unusual adventure and risk-taking that began with the most remarkable story.

.

Looking back now across almost half a century, John can still not quite believe what happened: ‘We just had incredibly bad luck.’ For as a young man in 1961, he lost his closest friend, Richard Mason, who became the last Englishman to be killed by an undiscovered tribe in the Amazon.

.

I first met John 30 years ago when I was planning my own expedition to Peru to look for Inca ruins. He lived then, as he still does, in a quiet residential Kensington square. It was gracious and characteristic of him to advise me, as at that stage I had very little experience of my own. He led me down the dark hall of his house and then into a study lined with books about South America, with shafts of light coming down from high windows. In a curious way, that moment of entering his study with him felt like the first step in the process of discovery.

He told me part of the story then, and over the years I have filled in other sections, but it was only recently that we discussed at length not only the tragic events of the 1961 expedition but his later quest to find the perpetrators.

.

The expedition had begun so well. They had been room-mates at Oxford and had already developed a taste for exploration: Richard had crossed South America by Land Rover, while John had managed to get a berth on a freighter to Peru. They recruited a third member, the unlikely figure of Kit Lambert, an old schoolboy friend of Richard’s who was later to be the Who’s manager, and set off.

They had been room-mates at Oxford and had already developed a taste for exploration: Richard had crossed South America by Land Rover, while John had managed to get a berth on a freighter to Peru. They recruited a third member, the unlikely figure of Kit Lambert, an old schoolboy friend of Richard’s who was later to be the Who’s manager, and set off.

At first the three young men, all in their twenties, felt they were living a wonderful adventure. By night they slept in hammocks; by day they mapped the beautiful and uncharted country along the Iriri River, having fun naming the lakes and hills after their girlfriends, just as a blameless river had been called after Theodore Roosevelt’s son Kermit when the ex-president led an expedition to the Amazon in 1913.

.

Their technique for getting through the jungle was simple. One of them would lead the path-cutting team of wood cutters. Aiming at a distant tree as a sightline, the leader would crash and hack his forward through the undergrowth, while two men widened the trail behind and the others followed.

John remembers it vividly: ‘Sometimes we shot game – wild turkeys or tapirs – but generally we ate little and lost weight. We became pale from rarely seeing the sun, and were covered in bites and scratches. The compensation for all this effort was the beauty of virgin rainforest and the knowledge that no Westerner had ever trodden there before.’

‘Richard was a wonderful leader. His Portuguese was poor, but his hard work and optimism commanded respect and inspired the men even when the going was toughest.’

Yet progress proved slower than expected. Their stocks of food started to run down and John was dispatched to Rio de Janeiro to get more supplies and drop them back by parachute.

‘I had no money. To get to Rio, I had to barter a bottle of whiskey with a pilot, and then hitchhike my way from the airport into the city – where I found myself in the middle of an attempted coup. The whole air force had been grounded. Somehow I managed to get an air-sea rescue team to help us and found myself flying back across the jungle in an enormous seaplane to be dropped off with the new supplies. Then we ran into a lightning storm. It was a surreal experience, seeing the lightning surround us and illuminate the jungle canopy by night.’

‘In the middle of the storm, the co-pilot came back into the cargo-hold to tell me that they had picked up bad news on the radio. While I’d been away, the expedition had been attacked and someone had been killed. At that point they didn’t know who.’

Only on landing did John discover what had happened. Richard Mason had been alone and going back down a trail they had previously cut. After months of exploring what the expedition had been told was uninhabited jungle, they had long stopped worrying about Indian attacks. But that is exactly what seemed to have taken place. The others had come across his body carefully laid out on the path, surrounded by 40 arrows and 17 heavy clubs. A bag of sugar was spilled nearby, untouched – as was a lighter. Nothing had been taken.

Only on landing did John discover what had happened. Richard Mason had been alone and going back down a trail they had previously cut. After months of exploring what the expedition had been told was uninhabited jungle, they had long stopped worrying about Indian attacks. But that is exactly what seemed to have taken place. The others had come across his body carefully laid out on the path, surrounded by 40 arrows and 17 heavy clubs. A bag of sugar was spilled nearby, untouched – as was a lighter. Nothing had been taken.

John found Kit Lambert in a complete and understandable state of shock. In today’s culture, Kit would have been more of a candidate for I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here than an actual expedition to the jungle. In later life he led a flamboyant and camp rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle with The Who.

.

The two men’s main concern was that there might be a further attack, so they hurried with the rest of their team to the relative safety of the one air-strip they could reach, Cachimbo, which John remembers as being ‘as isolated in the jungle as a small island in the South Atlantic’.

The Brazilian authorities flew in some medics and a platoon of ‘jungle troops’ – who, it seems, looked like they would have been more at home in the nightclubs of Rio. John asked if the body could be cremated. He was told that first there would have to be an examination to make sure that he hadn’t been killed by other members of the expedition; they all had to return to the scene of the death.

For John, it was a terrible journey: ‘We walked sombrely back along that familiar trail, sleeping at an old camp site. I remember it all as dreamlike, with the landmarks along the trail seeming unreal and the once-cheerful camp gloomy and strangely sinister. The medics embalmed Richard’s body and we carried it out, wrapped in canvas and slung under a pole, for eventual burial in the British cemetery in Rio de Janeiro.’

While like Kit, John was still in deep shock, he did try as best he could to rationalise his friend’s death. As Kit and he agreed, at least it had been almost instantaneous – it could as well have been a crash in one of the fast cars that Richard was so fond of driving.

And then John did something which some might find surprising. He decided to leave a gift of machetes for the unknown attackers, hoping that they would conclude that the white men were well-intentioned. This was in the tradition of earlier Amazon explorers like Colonel Rondon.

The question that naturally haunted John was how the attackers had come across Richard in supposedly uninhabited jungle: had they seen the smoke flares lit by the team for several days to guide John’s plane when it made its expected parachute drop – and were they from an unreported village nearby or a long range hunting party from tribes known to be living in the far distance?

For many years it remained an unresolved mystery. At least by carrying one of the jungle arrows back to an academic in Oxford (‘I felt very conspicuous on the train’), John was able to get an identification for the tribal group who had committed the murder: the Panará, at that time uncontacted by the outside world, but feared as savage and violent by neighbouring Brazilian tribes who called them ‘The Men With Heads Cut Round’ because of their pudding bowl haircuts.

In the decades that followed, John continued working in other areas of the Amazon and became a well-known expert on its history. It was not until 40 years later that he finally came face to face with the particular tribe who had killed Richard.

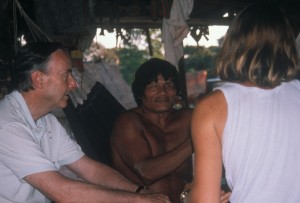

‘I assumed that all the Panará involved in Richard’s death would by now be dead, and that their descendants would have forgotten that distant ambush. They had suffered too many calamities of their own since then. Within two years of their first face-to-face encounter with the outside world in 1973, their numbers had fallen from 600 to 80. They were also forced off their tribal land by gold prospectors and cattle-ranchers. The Brazilian Government’s Indian Service had restricted access to them as a result. But when by chance we were able to reach the new Panará village when visiting another tribe nearby, I found that they did remember that first contact with a white man.’

With great good luck, one of the three people in the world who could speak the Panará language, anthropologist Elizabeth Ewart, was at the village when he arrived, so could translate. She told the tribe that John was a friend of the man they had killed and they became worried and apprehensive. Their leaders revealed that it had indeed been a long distance hunting party veering far from their usual path in search of Brazil nuts who had come across Richard in the jungle – or rather had come across the path the expedition had been cutting which, as John says, must have seemed like a motorway. They had waited beside it until they heard the ‘swish’ that Richard’s jeans made from far down the path as he approached. One man said that the hunters had called out ‘come here’ to Richard, and when he had not understood, they had killed him.

With great good luck, one of the three people in the world who could speak the Panará language, anthropologist Elizabeth Ewart, was at the village when he arrived, so could translate. She told the tribe that John was a friend of the man they had killed and they became worried and apprehensive. Their leaders revealed that it had indeed been a long distance hunting party veering far from their usual path in search of Brazil nuts who had come across Richard in the jungle – or rather had come across the path the expedition had been cutting which, as John says, must have seemed like a motorway. They had waited beside it until they heard the ‘swish’ that Richard’s jeans made from far down the path as he approached. One man said that the hunters had called out ‘come here’ to Richard, and when he had not understood, they had killed him.

‘I learnt,’ said John, ‘that doing so has always been the Panará way. Their word for “stranger” – for any non-Panará – is the same as for “enemy”. It was also an old Panará tradition for every member of a party that killed someone to leave his weapons beside the body.’

None of the original killers were still alive, but one old women revealed to John that she was the widow of the recently deceased Chief Sokriti, who had been one of the hunting party. She was able to give more details: that the hunters had removed Richard’s revolver – for signalling in case he got lost – but, not knowing what it was, had tried to smash it. They also clubbed something ‘shiny and mirror-like’ – his cigarette lighter, which the others later found near his body.

John asked about the machetes he had left there and found that, as he had hoped, they had been accepted as peace tokens. To his surprise – given that Amazon Indians are not given to niceties of gratitude or sympathy – one “gentle giant” called Teseya even told him: ‘We killed your friend in the old days when we did not know white men. We did not know that there are good white men and bad white men.’ He named the good white men who had helped the tribe to return to part of its lands. ‘You are a good white man. You may come back.’ John took this as a form of apology, even remorse, for the ambush 40 years before.

John asked about the machetes he had left there and found that, as he had hoped, they had been accepted as peace tokens. To his surprise – given that Amazon Indians are not given to niceties of gratitude or sympathy – one “gentle giant” called Teseya even told him: ‘We killed your friend in the old days when we did not know white men. We did not know that there are good white men and bad white men.’ He named the good white men who had helped the tribe to return to part of its lands. ‘You are a good white man. You may come back.’ John took this as a form of apology, even remorse, for the ambush 40 years before.

On leaving the Panará, John again flew over the Iriri river country that he had seen all those years before, much of it now looking like a lunar landscape from the damage left by cattle ranchers and soya farmers. By ironic coincidence the Panará have ended up living in precisely that area where Richard Mason was killed – then a bit of their distant hunting ground, but now one of the last bits of forest left to them.

As John has pointed out in his recent book, Tree of Rivers: The Story of the Amazon, there are however some optimistic gleams of light through the undergrowth. Since the 1960s the population of Amazon Indians has quadrupled, and there is now more respect for them in Brazil as the natural custodians of the planet’s most important lung. Many Indians that have had contact with outside society, after seeing how the West lives, have chosen to go back to their own way of life. And even today, there are still at least thirty Indians tribes in Brazil who are only known because they have been seen from the air, and have never been contacted.

He still bears no bitterness to the Panará over the death of his friend: ‘We were trespassers in their forests after all. The Brazilian Indian service have a saying for expeditions like ours: “die if you must, but never kill.” I do wish though that they had given Richard the time to convince them, even by sign language, of his good intentions, as I’m sure he would have.’

———————————————-

A version of this article was first published in Oxtravels, an anthology of travel writing for Oxfam

John’s book Tree of Rivers: The Story of the Amazon is published in paperback by Thames and Hudson