Long-standing readers of this blog will know that I rarely touch on films – despite being, among other things, a filmmaker.

Long-standing readers of this blog will know that I rarely touch on films – despite being, among other things, a filmmaker.

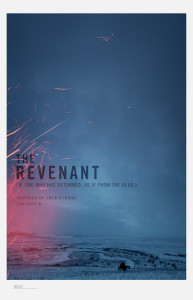

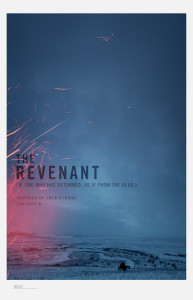

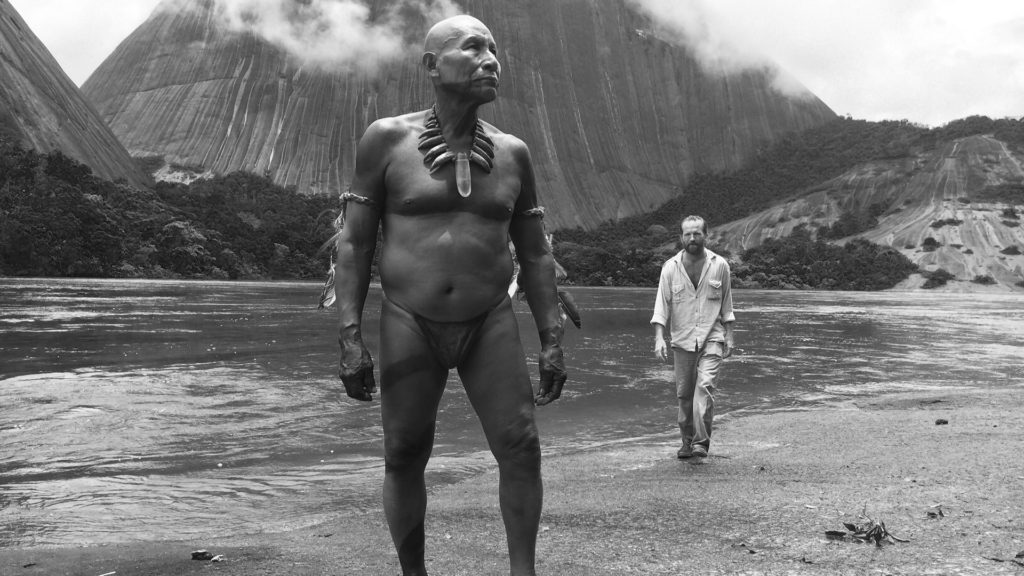

But then The Revenant is a rare film and moreover, a film about wilderness, the exploration of which is very much the theme of this blog.

.

It is also a reminder of how films need not be formulaic; how a bold director can rework and reimagine a mythic landscape – in this case, a wild west, or perhaps more accurately a wild north as we are in American fur trapping country of a brutal cold.

Alejandro G. Iñárritu finds the lyrical interstices of landscape. The moment you look up into the trees or the mountains. Most directors use a landscape shot to frame a sequence, usually at the start and end – as Quentin Tarantino does in his new Western, The Hateful Eight. Iñárritu edits his landscape shots to disconcert the viewer during the scene – to give the suggestion that the story is much bigger than the human one.

In some ways, his rule-breaking reminds me of what Terrence Malick did in Days Of Heaven – and like that film, a different way of working prompted mutiny from some of his crew. Film-making is so often done by default – there’s an elegant shorthand that has been involved for every type of sequence or narrative – that if anyone tries to escape that, they are rolling a rock uphill or, like Herzog in another movie that broke the mould, trying to take a ship over the mountain.

In some ways, his rule-breaking reminds me of what Terrence Malick did in Days Of Heaven – and like that film, a different way of working prompted mutiny from some of his crew. Film-making is so often done by default – there’s an elegant shorthand that has been involved for every type of sequence or narrative – that if anyone tries to escape that, they are rolling a rock uphill or, like Herzog in another movie that broke the mould, trying to take a ship over the mountain.

Iñárritu already showed in Birdman that he has a virtuoso mastery of camera and narrative rhythm (and ability to win prizes, which he certainly should for this); but whereas that was a lighter, theatrical piece, here he applies his talents to an elemental story of survival and revenge. DiCaprio holds it together well and Tom Hardy is a magnificently gnarly Texan; Domhnall Gleason’s captain has a documentary plainness to him that is as good as anything in Barry Lyndon, a film with similar lacunae of still moments.

This is a film about what it’s really like to engage with wilderness – the bloodiness of it and the bloody mindedness needed to survive. And of the beauty of elemental moments. It’s not a film for the fainthearted – but then they never did get out and about much anyway.

——————

The Revenant is released tomorrow on Xmas Day in the States, about the least appropriate festive film of all time (though The Hateful Eight is released the same day); and in the UK in the New Year. see trailer

![20160621_170716[1]](https://www.thewhiterock.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160621_1707161-300x168.jpg)

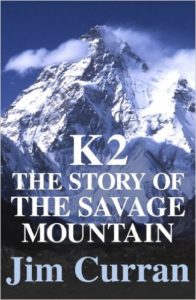

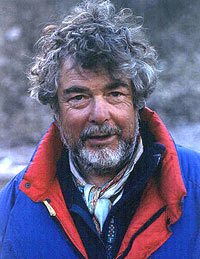

I was very sorry to hear that Jim Curran had died. He was an ebullient and kind figure who was generous with his help – and whisky – to writers like me who were less familiar with the mountaineering world. When I wrote

I was very sorry to hear that Jim Curran had died. He was an ebullient and kind figure who was generous with his help – and whisky – to writers like me who were less familiar with the mountaineering world. When I wrote

![20160405_163959[1]](https://www.thewhiterock.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/20160405_1639591-e1460750474252-168x300.jpg)