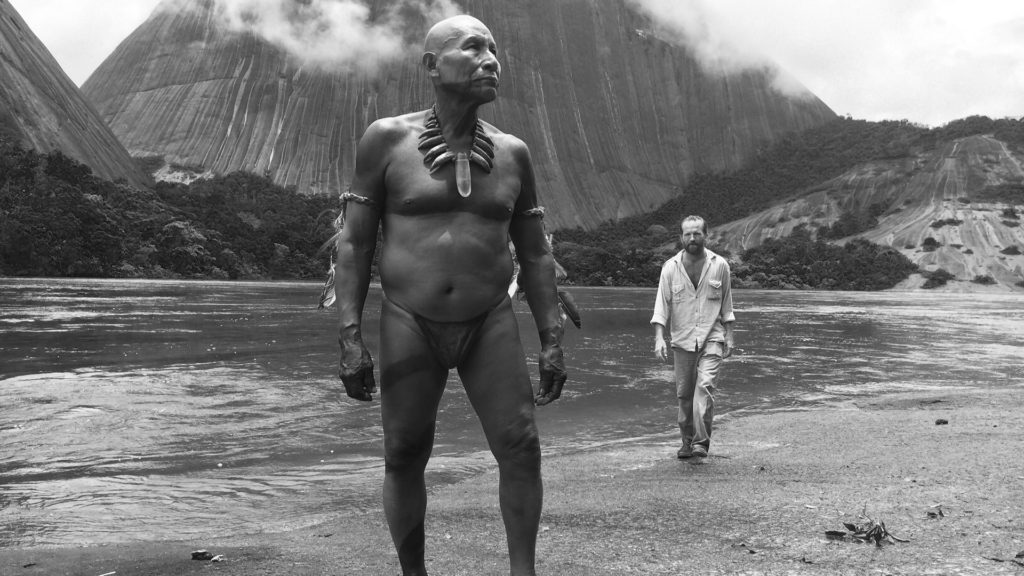

American Honey

So American Honey is as good as they say it is. I’m suspicious of critically acclaimed indie movies. They can be austere and intellectually respectable – like Cormack McCarthy’s The Road – and not terribly watchable. Particularly when they are almost 3 hours long.

So American Honey is as good as they say it is. I’m suspicious of critically acclaimed indie movies. They can be austere and intellectually respectable – like Cormack McCarthy’s The Road – and not terribly watchable. Particularly when they are almost 3 hours long.

But from the first beguiling frame, this is a masterclass both in direction and cinematography.

It’s shot in an at first brutal 4:3 aspect ratio – like an old school TV film, so almost square – and a reminder of how we usually like to soften out the horizons of a story in widescreen. The effect, together with the strong and harsh colour timing, is to make it look like some of William Eggleston’s cibachrome prints of the Deep South – motel bedrooms (much of the movie is shot in motels or the crew van or lost American suburbs), kids in supermarket checkouts, the shock of going outside onto bright sunlit grass. There is a fabulous scene – which would have been clumsy in less assured hands – when the two lovers chasing across a suburban lawn set off the sprinkler against an irradiated sky.

From the moment that newcomer Sasha Lane (the director cast her off the streets) appears on screen as Star, she holds it, often in close-up, along with Shia LaBeouf’s brooding and vulnerable bad boy presence. That is when alpha bad girl Krystal (played by Riley Keough, Elvis’s granddaughter) isn’t putting both of them in their place, a performance made somehow more aggressive because she is usually semi-naked when doing so.

The plot is freewheeling in a very good way. But the central premise is that Star is picked up by a van load of kids all trying to make money by hustling and selling magazines, and partying across America.

Where director Andrea Arnold opens it up is with the silences and interstitial spaces of glimpsed life from the van – not just white trailer trash America, but stray birds and dogs and lost children and, in one memorable scene, the oilfields burning at night. There is sadness and hope echoing round Star as she travels across America with a cohort of lost souls. It’s a film about female freedom and loss.

Is it the best film of the 21st century by a woman director? Undoubtedly. And despite the TV ratio, a film that absolutely needs to be seen in a cinema so you can get lost in it yourself.

![20160621_170716[1]](https://www.thewhiterock.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160621_1707161-300x168.jpg)