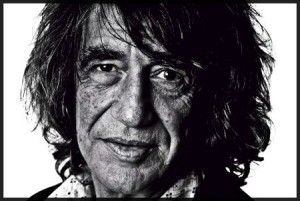

Regular readers will remember my review of Howard Marks’s book about his adventures and high times in the drugs trade, which I suggested signalled a new form of travel book – the ‘how am I going to get through customs’ genre. Another remarkable example of this was Marching Powder, ghost-written by Rusty Young about the hair-raising experiences of a drug dealer in a Bolivian jail and set to be a major motion picture, with Brad Pitt’s involvement.

Now comes Mark Dempster’s Nothing To Declare, ably ghostwritten by Matthew Huggins, which is considerably grittier than either of the above. Dempster does slightly less glamorous travel – though there is a funny bit where he tries to cross the Himalayas to a Nepalese village when stoned which is clearly not recommended in the manual – and is more Sweeney than Miami Vice.

Connoisseurs of the genre will still notice one or two similarities: there is always a moment when, just like the hero of Goodfellas, paranoia overtakes the life of Riley and the helicopters start circling overhead.

Dempster also does the ‘it’s just become a day job shtick’ well, when he describes ‘the same daily routine, the same grind: up at eight, drink, stock up on Crucial Brew, deal, opium, drink, deal, smoke hash, deal, line of coke, deal, line of coke, Brian [his main supplier], bottle of wine, Sprog [bodyguard and drinking mate, trouble], fight, opium, drink, sex with girlfriend Lesley, drink, drink, drink, drink – pass out. That was it – days into weeks into months until a whole year had vanished.’

Thinking of doing a hard-core writers book which would describe my day, which also begins at eight but otherwise has few similarities: cup of tea, watch a rerun of Frazier on Channel 4, bacon sandwich, few e-mails, cup of coffee, write as much as I can before I get bored, phone girlfriend, pop over to deli across the road for a chat, have a Scotch egg or pork pie for lunch if I’m feeling like something extreme, salad if I’m feeling healthy and trying to go clean, do some more writing, do some more e-mails, uh, take some exercise, and let’s face it no one has got this far in the paragraph because it’s so dull….

This book reminds me a bit of those Alcoholics Anonymous meetings where every speaker tries to outbid the last one by declaring that ‘you think that guy did bad stuff – wait until you hear what I did!’

Dempster is quite remarkably candid – and often funny – about his lowlife, which does hit some truly frightening lows by the end. It never quite addresses the mystery of why some people feel the need to get so wasted – ‘an addictive personality’ is a very loose concept. But it certainly describes the consequences well.

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of panspermia: the theory that Fred Hoyle and others put forward almost 30 years ago that – very broadly put – life was distributed across the universe by meteorites.

Blown away by the quite phenomenal Nick Dear play The Dark Earth and The Light Sky about Edward Thomas, now showing at the Almeida Theatre on its first run.

Blown away by the quite phenomenal Nick Dear play The Dark Earth and The Light Sky about Edward Thomas, now showing at the Almeida Theatre on its first run.

A

A

Another dissolute memoir which turns out to be a travel book in disguise. It seems only a few weeks ago that I

Another dissolute memoir which turns out to be a travel book in disguise. It seems only a few weeks ago that I