This is a longer version of articles written for both the London Evening Standard and the Washington Post when The Lost City of Z was released .

“Writer and explorer Hugh Thomson argues that new movie The Lost City of Z gives a totally false impression of its real-life hero.”

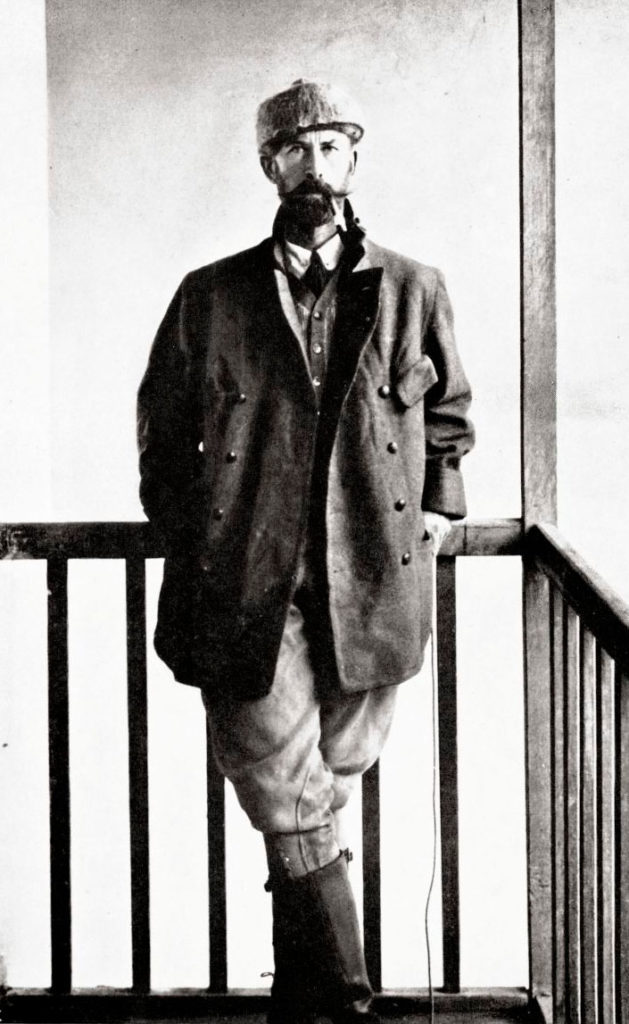

With many a jungle drum, this week sees the release and promotion of The Lost City Of Z. Based on the bestselling book of the same name by David Grann, the film proudly proclaims that it is ‘based on an incredible true story’ in which heroic British explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) ‘journeys to the Amazon and discovers the traces of an ancient, advanced civilization’. And yet it is a quite bizarre distortion of the truth, as anyone who has led expeditions to South America knows. Watch the movie and you might come away impressed by the dedication and perseverance of Fawcett. He is portrayed as a misty-eyed and misty-voiced romantic, inspired by Kipling’s poem to ‘Go and look behind the ranges – Something lost behind the ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!’ The movie is played out as one long elegy for his death, with accompanying strings.

With many a jungle drum, this week sees the release and promotion of The Lost City Of Z. Based on the bestselling book of the same name by David Grann, the film proudly proclaims that it is ‘based on an incredible true story’ in which heroic British explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) ‘journeys to the Amazon and discovers the traces of an ancient, advanced civilization’. And yet it is a quite bizarre distortion of the truth, as anyone who has led expeditions to South America knows. Watch the movie and you might come away impressed by the dedication and perseverance of Fawcett. He is portrayed as a misty-eyed and misty-voiced romantic, inspired by Kipling’s poem to ‘Go and look behind the ranges – Something lost behind the ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!’ The movie is played out as one long elegy for his death, with accompanying strings.

The exploration of the Amazon has been one of the epic undertakings of the last few centuries and is still ongoing: uncontacted tribes are still being found in the jungle. It has seen many heroic figures. But Fawcett was not one of them.

You will search the anthologies of exploration in vain for a mention of his name. Later explorers have found him something of an embarrassment. He is not listed in most of those anthologies for one simple reason: he never discovered anything. Moreover, he was a fantasist who believed in the occult and the Theosophy of Mme Blavatsky, so is regarded – and this is to put it kindly – as a complete flake. If anything, he is thought of as the Lord Lucan of the exploring world, whose most dramatic achievement was to get himself lost.

In the movie, Fawcett is portrayed as a matinee idol who single-mindedly pursues a noble quest, not as a grandstanding publicist. Equally misleading is the way in which he is shown as the only voice who stands up for the Indians he encountered, while all around him less enlightened old codgers proclaim their savagery. He makes a passionate speech in the Indians’ defence at the Royal Geographical Society (‘the native does deserve our sympathy’) and comes across as being enlightened and liberal in his views.

In the movie, Fawcett is portrayed as a matinee idol who single-mindedly pursues a noble quest, not as a grandstanding publicist. Equally misleading is the way in which he is shown as the only voice who stands up for the Indians he encountered, while all around him less enlightened old codgers proclaim their savagery. He makes a passionate speech in the Indians’ defence at the Royal Geographical Society (‘the native does deserve our sympathy’) and comes across as being enlightened and liberal in his views.

But the reality is rather different. The distinguished historian of the Amazon, John Hemming, has described Fawcett as in fact having ‘ugly racist notions about the Native Americans’. Fawcett described one tribe he encountered as ‘large, hairy men, with exceptionally long arms, and with forehead sloping back from pronounced eye ridges – men of a very primitive kind… villainous savages… great apelike brutes who looked as if they had scarcely evolved beyond the level of beasts.’

Nor is the argument that he was just ‘of his time’ admissible. There were plenty of contemporary explorers of the Amazon who recognised the qualities of the indigenous people. Theodore Roosevelt, no less, an explorer before he became president, had been impressed by precisely the same Indian tribe of Nambiquara.

As David Grann admits in his book – although you will find nothing of it in the film – Fawcett was deeply conflicted about his suspicion that there might once have been an earlier civilisation in the Amazon. He could not reconcile this with his poor opinion of the Indian tribes, so postulated the existence of ‘white Indians’ who had in some way travelled across the Atlantic from Europe and brought civilisation with them. Hemming has described Fawcett as a Nietzchean explorer, who sprouted ‘eugenic gibberish’ and was obsessed with the exotic and the occult.

Percy Fawcett was first sent to Bolivia and Brazil to do map surveying work in 1906, seconded from his duties as a British officer. He returned in 1914, after having heard stories about a huge ruined city ‘said to have been seen by Portuguese bandits north of Minas Gerais in 1743’. Even by the standards of South America, that is old and second-hand information, from an unreliable source.

Percy Fawcett was first sent to Bolivia and Brazil to do map surveying work in 1906, seconded from his duties as a British officer. He returned in 1914, after having heard stories about a huge ruined city ‘said to have been seen by Portuguese bandits north of Minas Gerais in 1743’. Even by the standards of South America, that is old and second-hand information, from an unreliable source.

But his potential sponsors at the Royal Geographical Society lapped it up. This was an age of heroic exploration, when the poles had just been reached and Machu Picchu discovered. Fawcett received the financial backing to pursue the glory that he had never found in his military career. He talked evocatively of how there might be ‘ruins incomparably older than those in Egypt’. Naming this chimera as ‘the lost city of Z’ showed his flair for publicity – and no wonder Hollywood has finally come calling, even if they have taken a century to do so.

When Fawcett disappeared in Brazil in 1925, together with his 21-year-old son Jack and another companion, it caused a public outcry and journalistic sensation. A series of privately-funded expeditions were mounted to find him. Occasional sightings of a lone white man somewhere in the jungle – even if thousands of miles from where Fawcett had last been seen – were enough of an excuse for editors of the day to raise the story again.

What most likely happened to Fawcett – again, not something you will learn from the movie – has been painstakingly re-created by distinguished Amazon historian John Hemming, in his 2003 book “Die If You Must,” and documentary-maker Adrian Cowell, in his 1960 book “The Heart of the Forest.”It seems that Fawcett’s racism led him into ‘dangerous attitudes to the Indians’, risking both his own life and that of his son. He recognised that tribes could be naturally hospitable; but failed to recognise that they also expected any visitors to be equally liberal.

Previous and current expeditions to the Amazon would always take quantities of presents. Fawcett did not, while still availing himself of anything the Indians could give him. Moreover George Dyott, the leader of one of the expeditions sent to find Fawcett after his disappearance, was told by Indians that Fawcett had broken an unwritten rule of forest travel. He had seen two canoes moored up on the back and simply taken them. Naturally the Nahukwá, whose canoes had been stolen, did not react well.

.

Likewise when Fawcett shot a duck – and much is made in the movie of his prowess as a marksman – he refused to share it with his Indian helpers. He also struck a young Indian boy who was playing with his knife. As Hemming remarks, ‘striking an Indian in anger is a deep insult. The Xingu Indians are infuriated by any aggression against a child, since they are deeply affectionate parents… And native hunters invariably share out their game.’

Brazilian anthropologists the Villas Boa brothers – legendary in Amazonia for their longstanding work protecting the Indians – commented that ‘Fawcett was the victim, as anyone else would have been, of the harshness and lack of tact that all recognised in him.’

So why is none of this in the film? And how is it that an incompetent who never achieved any discoveries – and was a racist blunderer to boot – has suddenly got the full Indiana Jones treatment?

Much of the answer lies in the original book by David Grann, published in 2009. This is far more intelligent and nuanced than the movie, as one would expect from a staff writer on the New Yorker. But even in that, the process of mythologisation has already begun – and some of what David Grann wrote tongue-in-cheek has been taken at face value.

Much of the answer lies in the original book by David Grann, published in 2009. This is far more intelligent and nuanced than the movie, as one would expect from a staff writer on the New Yorker. But even in that, the process of mythologisation has already begun – and some of what David Grann wrote tongue-in-cheek has been taken at face value.

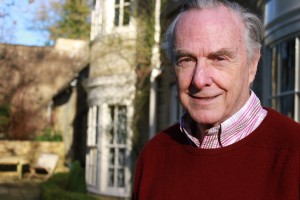

John Hemming, as the acknowledged expert on the history of the Amazon, was one of the first people that David Grann consulted about Fawcett. In The Lost City Of Z, Grann describes how he went to London and met him at the Royal Geographical Society – and how in writing the book, he ‘would have been lost without Hemming’s three volume history on the Brazilian Indian’.

So Hemming was puzzled when the book was published to find that Grann had ignored or inflated so much available material about Fawcett. In a review for the Times Literary Supplement, he commented that Grann had been seduced by the ‘jungle as green hell’ genre of travel writing, with fanciful pages about ferocious piranhas, huge anacondas and even cyanide-squirting millipedes. Whereas Grann suggests that as many as 100 people lost their lives in search of Fawcett, Hemming corrects the record: one person died. He went on to note that Fawcett explored a very small area of the Amazon, far less than many others. He self-mythologised to an unusual degree, presenting quite mundane journeys in the jungle as if they were Homeric odysseys, even if they were along previously travelled routes.

.

John Hemming has led many expeditions to the Amazon himself and his conclusion was damning:

‘It is a pity that a writer as good as Grann chose to study this unimportant, disagreeable and ultimately pathetic man. It is an even greater pity that he decided to inflate and distort so much of this sad story.’

To be fair to David Grann, the playfulness of his tone is a mitigating factor. He presents the world of the explorer as if it is more hyperreality than actual, which in Fawcett’s case it was.

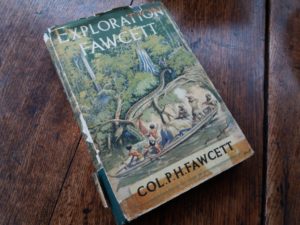

As a boy I had a copy of Exploration Fawcett, a posthumous collection of his writings. The cover shows an illustration that Fawcett’ drew of a monstrous anaconda as long as a canoe menacing the intrepid explorers and their Indian helpers as Fawcett raises a gun to shoot it. ‘Hardly waiting to aim,’ he recounted, ‘I smashed a .44 soft-nosed bullet into its spine, ten feet below the wicked head.’

One should remember that Fawcett was inspired in his descriptions of his jungle journeys by adventure novels such as Jules Verne’s La Jangada and the works of Rider Haggard. All featured trusty companions, unreliable natives and clues given by some ancient chronicle. The relationship between Edwardian writers and explorers was a symbiotic one. Arthur Conan Doyle knew Fawcett well (they shared an interest in spiritualism), and he based The Lost World on some of Fawcett’s fanciful accounts. ‘Isn’t anything possible in South America?’ Conan Doyle once remarked, and it became a place where the imagination was licensed to recount the wildest of tales, whether presented as fact or fiction. So, to a certain extent Fawcett’s tall stories – and now Hollywood’s – have given the world a version of exploring in the Amazon that it wanted and could recognise from fiction, however far from the truth it may be. The movie presents a cartoon Amazon where human skulls line the entrance to the Indian camp.

Grann himself is self-deprecating. He admits that he knows nothing of the jungle and, to begin with, little about Fawcett. As a travel writer, he adopts the approach of the ingénue: ‘Hey, I’m just from New York. I don’t know much about this, but I’m going to tell you anyway.’ This allows him to present some of Fawcett’s more far-fetched claims as if he is a kid enjoying the antics of a carnival artist on stage. So what if the guy claims to be the strongest man in the world. Who cares if any of this is true or not when it’s so much fun?

However, any such subtleties have been completely lost in this clumsy adaptation for the screen by director James Gray, who has taken Fawcett at face value. The narrative compulsion to make Fawcett a hero has won out over the far more interesting story of how a fantasist managed to persuade the world that he was doing something of significance – a Billy Liar of the Amazon.

Almost everything has gone wrong in Gray’s clumsy adaptation for the screen. For a start, he has written his own script and then filmed it with great reverence – almost always a mistake.

There are some real clunkers in the dialogue:

‘What do you know of Bolivia.’

‘In South America?’

Well, yes, of course, it’s the Bolivia in South America, which other one did you think he was talking about! This is comic book stuff. Every line is either signposted or signalled. Guffaws erupted around me in the preview theatre when for the very first shot of Fawcett in the jungle we see a snake slithering between his legs. Nor does Charlie Hunnam’s leaden depiction of Fawcett help. He plays the character as if everything he says are his last words – which over a lengthy 140 minute movie, makes the whole experience feel like the longest dying pause in history.

At one point Fawcett proclaims, ‘it will be a long way before we reach Amazonia,’ and the long-suffering audience may well feel the same. What a shame that Benedict Cumberbatch did not play the part, as at one point envisaged: he could have brought out more of Fawcett’s flawed character and disturbed hinterland. James Gray has pretensions to being a film auteur – but this is a movie that wants to be Apocalypse Now and ends up as Monty Python in the Jungle.

.

The only virtue of this lumpen behemoth of a film is if it draws attention to the unfolding discoveries in the Amazon at the moment. For although Fawcett may have done so for all the wrong grandstanding reasons, his suspicion that there may have been earlier civilisations in the Amazon has proved correct (and this was the saving grace of David Grann’s original book, which helped draw attention to recent archaeological findings).

The problem in the past was that, for obvious reasons, while great Andean civilisations like the Incas could build in stone – and so Machu Picchu, for instance, has been magnificently preserved – in the Amazon, the only available material was wood; however grandiose the civilisation, it naturally rotted away. Yet recent archaeological techniques have revealed how pre-Columbian tribes successfully converted the shallow topsoil of the rainforest into rich black earth – and has given credence to early accounts by conquistadors of great civilisations they glimpsed when first floating down the Amazon.

When I led expeditions to the Peruvian Andes from the 1980s on, I also went to John Hemming for advice and he told me something which I’ve never forgotten: ‘That while anyone might be able to find a ruin in South America,’ – although even this does not seem to have applied to Fawcett, who never did – ‘it can take a lifetime to understand what it means.’

For the process of exploration should be as much intellectual as physical. Interpreting complicated new data about possible lost civilisations is a fascinating test of mental agility and one which Fawcett was ill prepared for. He was a serving army officer and as such was good at surveying the disputed border between Brazil and Bolivia. But he knew nothing of archaeology and anthropology and so when it came to his wild goose chases after scraps of unreliable evidence and theorising about the existence of early civilisations, he was way out of his depth.

There is an old and wise explorer’s maxim – ‘you only ever find what you are looking for’ – so that unless you have a profound knowledge of your subject, be it Inca or Amazon culture, you will never be able to interpret or indeed find anything of value.

Those who’ve travelled widely on the Amazon know that it is in reality mundane, soporific and almost dreamlike, with very little in the way of action ever occurring. It is perfectly possible to travel for days without seeing any wildlife, let alone ‘giant anaconda’, which will of course have been alerted by the noise of oncoming canoes. In its broader stretches, the Amazon is more green suburbia than green hell, where nothing happens, slowly.

Hollywood, of course, wants action and it also wants heroes. But even in a post-truth world, there is only so much distortion of the facts that is admissible. And in this case it is also unnecessary.

If the filmmakers had been looking for a real hero to make a movie about, they could have found one much closer to home. At the same time as Fawcett was getting lost in the jungle, the American explorer Hiram Bingham made some genuine and extraordinary discoveries of Inca ruins –Machu Picchu being just the most famous. He was also an academic at Yale, who had, unlike Fawcett, made scrupulous studies of the historical material, and was deeply sympathetic to the Indian population. Standing well over six foot in his Fedora and knee-length boots, it is he, not Fawcett, who was the original swashbuckling model for Indiana Jones. Moreover, in later life he married a Tiffany heiress, had seven sons and became a Senator. Plenty for Hollywood to get its teeth into.

There is a fascinating movie to be made about exploration in the Amazon. This isn’t it. Those wanting more illumination should see the Oscar-nominated Embrace Of The Serpent which came out last year, made by South Americans and with a silverine, elegant charm to which The Lost City of Z can only aspire.

And anyone heading out to a dinner-party this evening should perhaps remember to take a reciprocal bottle or face consequences from the natives. While those going to see the movie in its opening week may need sleeping tablets, resilient buttocks – and a healthy dose of scepticism.

In a curious way, the willful ignorance of this film echoes the willful ignorance of Fawcett himself. Why stick to the facts when you can play to a myth? But even if truth may sometimes be stranger than fiction, that is not a licence to invent it. For this is indeed an incredible story. But not a true one.

Hugh Thomson has led many expeditions to Peru, as recounted in his book The White Rock: An Exploration of the Inca Heartland, which was a New York Times Notable Book.

Follow Hugh on http://www.facebook.com/HughThomsonBooks and on Twitter @Hugh_Author

Great article, Hugh! I’ll read the book by Grann, with due caution. Might even watch the film, which sounds enjoyably bad. There are actually quite a few books about Fawcett – can you recommend any others? Is Grann the best?

To be fair, the average American moviegoer may not know where Bolivia is located. (And the same might well have been true of the average British army officer at the turn of the last century.)

John Lloyd Stevens is an excellent source of jungle discovery expeditions with astounding on-site illustrations by co-explorer Frederic Catherwood.

I enjoyed the film- it was a bit paint by numbers but it covered a huge area of his life and his motivations, it was also a story of decline, the derring-do of the British empire and particular type of hero. I think that he has been overlooked because he ‘failed’ but the film shows how he respected the cultures he found, in contrast to the other members of RGS. The class-based snobbery of the period is also well represented.