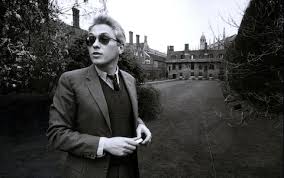

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

He certainly enjoyed being a Cambridge maverick. But he did also prove an extraordinary brilliant teacher and this of course is his true legacy.

A sometimes partial one – he could be unfair to those he excluded from his circle and I will always remember the shocked tones with which he once told me a student was doing a thesis on Tolkien – but if he engaged with you, it was a life transforming experience.

For Eric, the study of English literature mattered: in a heuristic way, in a way that constantly questioned one’s own responses and assumptions, in a way that affirmed what it is to be alive and to process mute swirls of consciousness into words on the page.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

The figure that inevitably comes to mind is that of Coleridge, standing in his study at Greta Hall with its big windows, looking out at a vista of mountains and space in which all seemed possible, but nothing ….was quite within reach. The central image in Eric’s biographia literaria would be of him pacing his study over New Court, listening to Talking Heads, chain-smoking and chain-drinking gin and tonics, engaging with his writers like a shaman summoning up spirit gods from the past with the aid of hallucinogenics (although harder drugs were one of the few vices Eric did not aspire to) but never quite able to wrestle them to the floor.

For Eric was suspicious of theory and suspicious of any critical conclusion that tied up a writer in a neat cardboard box and delivered it in gift wrapping to the reader. To use a theoretical term that he might not have approved of – now that he is no longer here to give a despairing glance at any solecism – he was suspicious of closure.

And this is not closure for Eric, despite the cruel, cruel way he was taken from us.

He lives on in the minds and hearts of those he taught. He was a mesmeric and powerful influence on many. He was a truly Socratic presence. And often a very funny and loyal one.

As we grow older, we collect the voices of those who’ve passed inside our own heads. I will hear him in my mind until the day I die, cajoling, exhorting and above all questioning, which surely is the true role of a critic in a world so complacent in its own certainties.

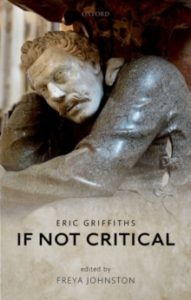

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

Posted on the day of Eric’s funeral in Cambridge, November 9, 2018

His rooms were surely above New Court – unless he moved.

I was one of Eric’s earliest students at Pembroke College during what must have been his first year of teaching after returning from America. He had a flat, or perhaps just rooms, in, I seem to remember, Orchard Street where he hosted a series of extraordinarily-stimulating practical-criticism sessions. He taught me for three years.

I still ponder some of the questions he asked, such as the significance of kisses ‘four’ in Keats’ LBDSM.

He had a powerful influence on me, and through me, I think, on the pupils I then taught.

As a fellow-northerner (and, indeed, Lancastrian), and given the fact that most of the other English students at Pembroke were public-school-boys from London the south-east, we had a certain affinity.

He was exceptionally kind to me during my four years in Cambridge. I sometimes had the pleasure of spending time with him alone when he used to drop the more waspish and theatrical aspects of his university persona and we often talked on (relatively) equal terms about our families and backgrounds and our experience of Cambridge.

It’s a pity that he has such a reputation as a ‘typically eccentric’ don as he was not in the least bit donnish, ivory-towered or superior. Quite the opposite.

Actually, his approach to criticism had a strong foundation in his Lancastrian upbringing. One advantage of being a ‘provincial’ is that the coterie values of the metropolis carry no weight with you. He therefore – a little like Lawrence, perhaps, as well as Eliot or Pound, or Newman or Empson, for that matter – saw himself at odds with much of what went on in this world, including Cambridge, and his venom towards its pretensions, shallowness and shoddy thinking, its ‘tendency to encourage a ‘flank-rubbing consensus’, in Leavis’s phrase, that disabled thought was real and deep-rooted and not a matter of mere show.

Like Leavis, he was a quintessential outsider, seeking to continue the tradition in Cambridge of thinking capable of subjecting English ‘culture and society’ to close ‘scrutiny’. To make Cambridge better than it was, in short, and work for the recognition by it and within it of centrally-important values. Like Leavis, too, and despite his later conversion and his affinity for writers like Newman and Eliot, he was in part a puritan

Similarly, his apparent rudeness and his definite acerbity were both sincere and authentic. Only if you have yourself gone through the process of being brought up in an ordinary Lancashire family and then being educated at somewhere like Cambridge can you appreciate how the colloquial, pithy aside is integral to your personality and is genuinely a part of your repertoire. To come out with such asides is simply to make audible the inner commentary of earlier aspects of your self, sceptical and iconoclastic by virtue of your upbringing, on your present self, actions and experiences.

One reason so many people disliked him was probably because he was so clearly right about their shortcomings and those of the institutions they served.

It was also difficult, given his impishness and his obvious ‘vices’, for many people outside his close circle to recognise the character, the seriousness and the scale of the task which he had set himself.

I wasn’t surprised that he became a Catholic as this clearly provided spiritual and moral support for what otherwise would have been a very lonely role.

He was first and foremost a teacher rather than a scholar because I think he realised that outside the sanctity of the ‘classroom’ in the world of ‘professional scholarship’ certain fundamental values had been irreparably compromised and he had no wish to compromise his own voice by joining that world in the ways that would have been required of him were he to be fully ‘recognised’.

You do get a sense reading his lectures of the intimacy of his engagement with his students and by implication the extent to which their fundamental honesty presents a challenge to the institutional setting in which they were delivered.

You also appreciate Eric’s deep integrity and his willingness to talk to students as equals. When he uses the odd obscure technical term or makes some esoteric reference, he is not showing off. These are simply part of nature. It is the media lens through which he was too often viewed that makes them seem showy or calculated. In the immediacy of the classroom they come across as invitations to debunk the very world that then sneers at them when they become public.

The pity is that there was, simply, no ‘organ’ to act as a true and faithful conduit of his words and thoughts in which he could happily be published. Which perhaps goes some way to explain his failure to establish himself as a ‘scholar’ or as a media figure. His entire being was at a tangent to these worlds and in entering them, he cut an awkward figure, was all angles and elbows apparently.

One of the great ironies of his having been hounded by the press (run largely by ex-public-school-boys) for his treatment of Trac(e)y (was that her name?) was that he was probably looking for the iconoclastic streak in this candidate for entrance to the college and seeking to establish that she was capable of viewing herself and the world with ironic and humorous detachment.

He obviously misjudged her capacity or willingness in this respect.

It was very telling that when later accepted into Warwick, Tracy was pictured clasping a copy of Toni (?) Morrison’s Beloved.

I was present at high table in Trinity once when Eric berated a Nobel-prize-winning mathematician for taking no interest in maths in schools. The other dons, on leaving the table, congratulated Eric on providing some great entertainment. Actually, he really meant it and knew that I would know he meant it.

In the worlds in which he spent so much time, for the sake of teaching and continuing a certain tradition, he was prepared to be endlessly misunderstood and misjudged.

None the less, there are innumerable students who now know what words like criticism, thought and integrity really mean, having themselves experienced at first hand what they sound like.

Eric was one of the few true thinkers of our age. That he is not more widely recognised in that age tells us a great deal about its limitations and must make anyone fortunate enough to have been taught by him even more keenly aware of the value of his example.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful appreciation Stephen

In fact Eric was not brought up by an ‘ordinary Lancashire family’. His parents were Welsh and he was brought up in Walton, Liverpool.