This article was originally published in Conde Nast Traveller

.

How difficult it can be to let go of the rope when travelling – to leave guide-books, maps and the official tour behind, and just cut loose to see where the waves wash you.

Fez is a more daunting place to do so than most. So labyrinthine is the walled Medina – the largest Arabic medieval city in the world – that official guides wait at its entrance to lead travellers in and more importantly out of its twisting alleyways and tunnels, home to 150,000 people.

Fez is a more daunting place to do so than most. So labyrinthine is the walled Medina – the largest Arabic medieval city in the world – that official guides wait at its entrance to lead travellers in and more importantly out of its twisting alleyways and tunnels, home to 150,000 people.

So I set forth with a certain sense of abandon on my first day, surrounded by a crowd of small boys who chorus ‘Qu’est-ce que vous cherchez?’ in the shrill voices of sparrows. A man is winding a thread down the wall of a street, twisting it to create not a lifeline to help me get back, but a braid for a belt.

I’m reminded of a video game my children play, Assassin’s Creed, which depends on complete disorientation within an Arab city. The illusion of helplessness is encouraged by the way the Medina funnels downhill; I feel I’m falling towards its centre down alleyways of bewildering complexity. As with Arabic calligraphy, there are no straight lines. Quite soon I’ve given up all attempt at ‘la orientation’ and am just letting myself be lured into anything that glitters: the street of slippers, with thousands of pairs stacked toe-out so that one can see the angle of curve on their embroidered ends; sheets of Berber jewellery laid out against red cloth; carpets from the nearby Middle Atlas; and rows of metal lamps hanging from the rafters with coloured glass inserts that catch and hold the light.

.

.

It is the lamps that remind me of something an African friend had told me when she knew that I was coming to Fez: ‘the city is like a geode rock – it seems brown and barren from a distance, but cut it open and there is an Aladdin cave of crystals on the inside.’

I linger in the woodcarving stores, for the smell of cedar and juniper wood, and also for the names that sound so much better when recited in French by the craftsman: ‘cèdre, arganier, genévrier, noyer, citronnier’. Stacked casually on the wall are daggers that look out of The Prince of Persia, silver-plated poignards with inlaid handles and a swashbuckling curve to the blade.

No one would linger in the nearby tanneries – so strong is the smell that sprigs of mint are provided for visiting westerners to hold to their noses, like French aristos passing the sewers of Paris. The view over the vats of dye in the heart of the city has become one of the defining images of Fez – and the day that they are removed to some anonymous suburb will be the sign that gentrification has arrived.

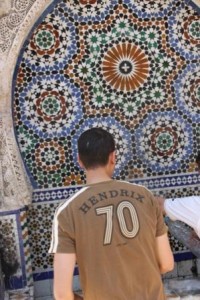

To enter the Bou Inania Medersa is to reach an oasis of space among the crowded streets. This 14th century religious complex has been recently restored to almost its former glory; although they have not been able to get the Fez river running across the courtyard as it once did, the kufic script does at least flow around the walls, along with the zellij designs typical of Andalusia and a fabulous turquoise minaret. It is one of the finest buildings in Morocco.

The response of the Medersa’s creator, Abu Inan, to the builder who quoted him for its astronomical cost (and who perhaps added, in best souk-style, “and that’s my best price”) was that “what is enthralling is never too costly,” a maxim on the lips of many other reproachful Fez stallholders faced by the clumsy bargaining techniques of Western visitors. I found them to be salesmen in the best sense, leaving me feeling satisfied even when what was meant to be “a best price” clearly wasn’t. My favourite line was that ‘listen, wherever you live in the world, if at any time you are unhappy with my (carpet / inlaid box / bag / ‘cashmere’ shawl) I will personally fly to your country and replace it for you. Because it is my father who made it.’ And a hand is gently laid on the heart.

.

.

Certainly compared to the strong arm tactics of the Marrakesh souk, Fez is an oasis of laid-back charm. When a Frenchman comes into one upmarket antique shop and uses an ornate silver-plated bowl as a convenient ashtray, the owner barely bats an eye. Chill-out music is playing in the nearby Café Clock, the bohemian meeting place of choice; on its roof terrace overlooking the Medersa, a few young Moroccans are strumming La Bamba to their kohl-eyed girlfriends.

Morocco has been bucking the fundamentalist trend in recent years. There are plenty of rhinestone T-shirts on display in the market, many female heads are resolutely un-scarved and the more tolerant practises of Sufism encouraged by Mohammed VI, king for the last decade.

It is Fez’s reputation as one of the historic centres of Sufism, the mystical tradition within Islam that has often been at odds with orthodox theology, that has drawn me to the city. I have visited Sufi shrines in Dagestan, Delhi and Ajmer and always been deeply impressed by the simple spirituality and acceptance of other religions characteristic of its practitioners. In recent years it has been much persecuted in hardline Muslim states: but here it still flourishes. As one Morocco cafe owner points out to me, this must be one of the very few cities in the Middle East where they can still have a Festival of Sufism every year.

.

Every time I seem to turn a corner in the Medina, there is a fountain with an inscribed religious saying. The association between water and Islam runs deep. An early Sufi saint from Fez, Ahmad Al-Badawī, remarked that “Sufi schools are like waves which break upon rocks: they are from the same sea, in different forms, for the same purpose.” At one such fountain a blind man is cleaning his bird cages, while a friend watches on to make sure that none of the city’s predatory and skinny cats take advantage of the moment to seize a songbird.

In recent years, the Medina has started to be restored and outsiders from both Marrakesh and abroad have moved in to help create some beautiful riad hotels and dar guesthouses. While once you could buy a small palace for £30,000, prices have now gone up accordingly and some of the longer term foreign residents have started to complain that the character of the Medina is changing. But this needs to be seen in context.

Of the 150,000 permanent inhabitants of the Medina, only 50 are foreigners. There are over 9000 courtyard houses. And while the occasional tractor or builder may break the “donkeys only” rule within the narrow streets, much of the city remains impressively unchanged to the casual outsider.

.

.

David Amster is a resident who has led the charge to make sure that it stays so. An Arabist and the director of the city’s American Language centre , he owns several beautifully restored houses in the Medina. He tells me that one night he passed an old family house to see its beautiful painted wooden doors being removed illegally. On discovering that the doors had been taken to Rabat a hundred miles away, David traced them there with the help of its antique dealers, and bought them back at his own expense to re-hang in the house.

He tells me the story over a cup of mint tea in the garden of the American Language centre, which despite its name does most of its business teaching foreigners Arabic. It’s one of the main gathering places for travellers passing through and also one of the very few places to be signposted, which is how I’ve stumbled across it. For a brief moment I toy with the idea of how nice – and impressive – it would be to learn Arabic, before consigning it to tennis, French and playing the guitar, all skills I have spent a lifetime aspiring to without ever managing to acquire.

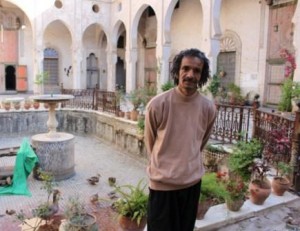

Towards the end of the day, I am beckoned into the doorway of what looks like a narrow house by a Moroccan with the drawn cheekbones and intense eyes of an artist, which is what he turns out to be. Abdelkhalek Boukhars is the custodian of the Glaoui Palace, once the Fez residence of the family described by Gavin Maxwell as the “Lords of the Atlas”, now a fabulous and dilapidated shadow of its former glory, with ducks and chickens in the empty fountains and an old Roberts radio blaring rai music from a prayer niche. Abdelkhalek has set up a small studio in the empty harem where he produces abstract calligraphic canvases of some skill.

Towards the end of the day, I am beckoned into the doorway of what looks like a narrow house by a Moroccan with the drawn cheekbones and intense eyes of an artist, which is what he turns out to be. Abdelkhalek Boukhars is the custodian of the Glaoui Palace, once the Fez residence of the family described by Gavin Maxwell as the “Lords of the Atlas”, now a fabulous and dilapidated shadow of its former glory, with ducks and chickens in the empty fountains and an old Roberts radio blaring rai music from a prayer niche. Abdelkhalek has set up a small studio in the empty harem where he produces abstract calligraphic canvases of some skill.

Leading me through the empty courtyards, he pulls what is clearly his favourite party trick: “I want you to imagine you are on a magic carpet and want to fly to Granada” — and opens a beautifully made wooden door to reveal some of the finest zellij work I’ve yet seen in the city, done in the playful late Nasrid style of Al-Andalus in Spain.

.

I wander onto my last encounter of the day, to which I’m drawn by a rhythmic chanting that rises above the noise of motorbikes accelerating and the evening call to prayer – the informal Sufi concert that happens nightly in one of the small gardens near the blue gate. Eleven white-robed musicians are chanting and playing a rhythmic paeanto Allah. Carpets have been spread out on the ground so the audience can relax. A cafe nearby is doing a brisk trade in mint tea and pigeon pastillas. I lie back and watch the swifts crossing the evening sky now as mauve as the painted windows of the Glaoui Palace, while the music keeps building steadily in power and complexity. A Moroccan nearby asks me if I support Manchester United, if I have met Alex Ferguson and is it true that he is both a manager and farmer, for does he not keep horses as well as footballers?

It’s payback time. I’m trying to find the door to the tiny but exquisite private guesthouse I left first thing this morning. I had carefully marked the alley that led to it, between a bakery and a pirate CD store. But now the shops are shut, the metal doors drawn, and all look alike. A group of boys break off from a game of football and cluster round me. After a long day, I’m in no mood for being mugged for small change or trinkets. But they recognise me even though I fail to recognise them, before they chorus in that sparrows’ twitter from the morning, ‘did you find what you are looking for?’ And they lead me back to my house in the centre of the Medina.

It’s payback time. I’m trying to find the door to the tiny but exquisite private guesthouse I left first thing this morning. I had carefully marked the alley that led to it, between a bakery and a pirate CD store. But now the shops are shut, the metal doors drawn, and all look alike. A group of boys break off from a game of football and cluster round me. After a long day, I’m in no mood for being mugged for small change or trinkets. But they recognise me even though I fail to recognise them, before they chorus in that sparrows’ twitter from the morning, ‘did you find what you are looking for?’ And they lead me back to my house in the centre of the Medina.

This article was originally published in Conde Nast Traveller – see printed version

all photographs (c) Hugh Thomson 2011

Beautiful. You sure know how to get lost in a very poetic way.

Tx Ali – Hugh

Hugh.. just wanted to thank you for taking the time to write this.. i am off to Fez in a month.. I am trying to seek out as much info as possible.. this has increased my excitement for my journey.. looking to go and take photos til i drop.. i feel slightly nervous about how I am going to get on but your explanation of the temperament of the locals has helped.. i will also hopefully be paying Mr Boukhars a visit.. i have read that you can gain access by loitering around the enterance and waiting for someone to let you in at a price.. it is likely i will use the nav on my phone to help orientate me and bare the brunt of the costs later!

Thank you, Hugh, for the wonderful article. Great description of Fes. Please note that I’m a linguist (used to be a Greek and Latin teacher) but not an Arabist…I was interviewed by Al Jazeera once and they wanted me to speak Arabic, but I didn’t because I was sure it would be “bad for business” 🙂 David A.