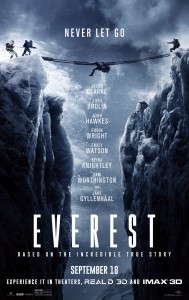

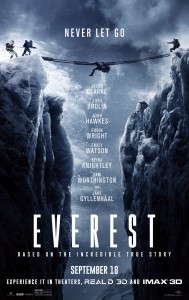

Everest as a film has perhaps been unfairly criticised for having some of the messiness of a real-life expedition – too many characters and an untidy ending – faults (and strengths) it shares with the other adaptation made from a Jon Krakauer book, Into The Wild. And it’s true there are moments the only way you can tell the men with frozen beards apart is by the colour of their product placement North Face jackets.

Everest as a film has perhaps been unfairly criticised for having some of the messiness of a real-life expedition – too many characters and an untidy ending – faults (and strengths) it shares with the other adaptation made from a Jon Krakauer book, Into The Wild. And it’s true there are moments the only way you can tell the men with frozen beards apart is by the colour of their product placement North Face jackets.

.

The class British scriptwriters – William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy – have fashioned a story which ostensibly has no links with the Krakauer book, but given that it was his Into Thin Air which made the 1996 tragedy on Everest so famous, his shadow looms large over it. He also makes an appearance in the film as an embedded journalist in the team who accompanies them to the summit.

The film hits one nail hard on the head – that some of the dangers which arise are the consequence of the new phenomenon of commercial guided expeditions up Everest, so that less competent mountaineers are able to attempt a summit they should arguably not be on. But they fail to bring out one crucial argument in Krakauer’s book: whereas in the past all members of a team would look out for one another, now the guides look out for the clients but who is looking out for the guides? Of those who die on screen in the film, three are guides and two clients.

There is one crucial moment when lead guide Rob Hall has an uncharacteristic failure of judgement and allows himself to escort a client up to the summit way past the cut-off point when they should already be returning; the sort of misjudgement that is easy to happen when people are hypoxic and under extraordinary stress. But also one that occurs when you are no longer dealing with a band of brothers but rather of responsible uncles with their nephews.

The filmmakers were lucky to have David Brashears on board, both because of his presence on Everest in 1996 at the time the tragedy unfolded (Brashears was making an IMAX film and his character is played by an actor in this one), and for his help on how on earth you make a movie at such challenging altitudes. While some sections were shot on Everest itself – in mid January, so freezing temperatures – which cinematographer Salvatore Totino described as extraordinarily difficult in the Hollywood Reporter – the Hillary Step, where much of the most intense dramatic action occurs, was recreated at Pinewood. As the second unit crew were shooting some remaining scenes of the film at Camp II on Everest, an avalanche struck, killing 16 Sherpa guides with other expeditions.

The filmmakers were lucky to have David Brashears on board, both because of his presence on Everest in 1996 at the time the tragedy unfolded (Brashears was making an IMAX film and his character is played by an actor in this one), and for his help on how on earth you make a movie at such challenging altitudes. While some sections were shot on Everest itself – in mid January, so freezing temperatures – which cinematographer Salvatore Totino described as extraordinarily difficult in the Hollywood Reporter – the Hillary Step, where much of the most intense dramatic action occurs, was recreated at Pinewood. As the second unit crew were shooting some remaining scenes of the film at Camp II on Everest, an avalanche struck, killing 16 Sherpa guides with other expeditions.

A facile criticism of the film is that this is such an exclusively male affair. This just mirrors the actual expeditions which were almost exclusively male – although it is true that the two female climbers are given paper thin characterisation – but also is a reflection of how a tunnel-visioned imperative to get to the top of something, regardless of disruption to family, is a not very commendable part of the male psyche. Scenes of the two wives back home – Rob Hall’s is played by Keira Knightley – and the way they react as events unfold on the mountain are handled deftly and movingly by Icelandic director Baltasar Kormákur, an interesting choice, given his indie background. The wives’ reactions are not nearly as forthright as those of the widows of some Everest fatalities, who have sometimes expressed bitterness in documentaries at the way their husbands put summits before family.

The movie succeeds in many ways – a particularly fine performance by Jake Gyllenhaal as rival, maverick guide Scott Fischer, and a stunning recapturing of the landscape of Nepal. See it in 3-D, so that, in the best traditions of filmmaking, the movie takes you there in a way which means you never, ever have to do it in real life – thank God. For one thing, the film amply demonstrates is that the death toll on Everest is not worth it. Anyone who wants to experience a sublime mountain moment can do so elsewhere below the death zone without putting their own lives – and others – at risk.

I was very sorry to hear that Jim Curran had died. He was an ebullient and kind figure who was generous with his help – and whisky – to writers like me who were less familiar with the mountaineering world. When I wrote my book about Nanda Devi, he gave invaluable advice.

I was very sorry to hear that Jim Curran had died. He was an ebullient and kind figure who was generous with his help – and whisky – to writers like me who were less familiar with the mountaineering world. When I wrote my book about Nanda Devi, he gave invaluable advice. But aside from his multiple creative achievements, one quality will always stand out for me about Jim – a quality that is not always a given in the focused, over-achieving world of mountaineering: he was extraordinarily generous and terrific company.

But aside from his multiple creative achievements, one quality will always stand out for me about Jim – a quality that is not always a given in the focused, over-achieving world of mountaineering: he was extraordinarily generous and terrific company.

The filmmakers were lucky to have David Brashears on board, both because of his presence on Everest in 1996 at the time the tragedy unfolded (Brashears was making an IMAX film and his character is played by an actor in this one), and for his help on how on earth you make a movie at such challenging altitudes. While some sections were shot on Everest itself – in mid January, so freezing temperatures – which cinematographer Salvatore Totino described as extraordinarily difficult in the

The filmmakers were lucky to have David Brashears on board, both because of his presence on Everest in 1996 at the time the tragedy unfolded (Brashears was making an IMAX film and his character is played by an actor in this one), and for his help on how on earth you make a movie at such challenging altitudes. While some sections were shot on Everest itself – in mid January, so freezing temperatures – which cinematographer Salvatore Totino described as extraordinarily difficult in the