As the Americans prepare to leave Afghanistan and here in Britain we hold a Defence Review, have we learned the lessons of our own failures there?

As the Americans prepare to leave Afghanistan and here in Britain we hold a Defence Review, have we learned the lessons of our own failures there?

Lockdown has given me plenty of time to reflect and I’ve been thinking recently a great deal about Afghanistan – perhaps prompted by the fact that the Americans may be about to withdraw completely from that country after 20 years of largely unsuccessful occupation since the invasion.

I was in the country for a brief and intense time in 2007 when I was filming for Channel 4 Dispatches and CNN. We saw a country that had been brutalised for decades by the Russian occupation, the ensuing civil war and then the American carpet bombing to ensure that their troops met no resistance. And a country which was becoming restive as the Allies seemed increasingly unable to help them rebuild, or for that matter interested in doing so once they had been distracted by Iraq.

At the time it seemed a pivotable moment to be there and with hindsight it is even more clear that the country was at a tipping point. For the first five years after the 2001 invasion, only a handful of British troops had died in Afghanistan. This had bred complacency.

Tony Blair had then made a momentous decision not long before we started filming. To demonstrate British military efficiency and willingness, he volunteered British forces to take over in the rural south of Afghanistan, near the porous border with Pakistan where the Taliban had retreated. So in 2006, 5500 British troops were sent to the province of Helmand. Blair’s defence secretary, John Reid, made the blithe assertion that he hoped the troops would leave in three years time ‘without a shot being fired’. He was wrong on both counts: it was to be another eight years before British combat troops left Afghanistan, in 2014; and they were to suffer many casualties. Over 450 British personnel were to die in the conflict, and far more were left suffering life-changing injuries.

Tony Blair’s decision came at just the wrong time. The mood in Afghanistan was palpably changing. The American military had made no attempt to ‘nation-build’ after their remarkably quick and successful invasion. Donald Rumsfeld at the Pentagon had explicitly opposed it, hoping that the ragtag collection of Northern Alliance leaders presided over by Hamid Karzai would do the job for them– despite the fact that most were warlords and had singularly failed to do so during the earlier civil war.

The Afghan population, who at first had largely welcomed the outing of the unpopular Taliban, had begun to realise that while money was swilling into the country to aid agencies, not much was getting through to them – and that the allies simply did not understand how the complicated tribal system of councils, the jirgas and shuras, could not easily be bypassed by parachuting in governors. Nor did it help that after the Russians had destroyed much of the irrigation system as part of a scorched earth policy, the opium poppy was left as the easiest and most valuable crop to grow. And nowhere was more opium being grown than in Helmand, just to add to the problems being faced by the British.

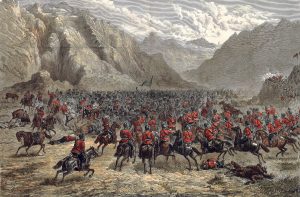

But there was another difficulty waiting for them, along with the opium. Tony Blair had made a terrible miscalculation. If he had forgotten that the British were still more hated than any other nation in Helmand, the locals certainly hadn’t. The Battle of Maiwand had taken place nearby in 1880, which had brought to an abrupt end the last attempt the British had made to control Afghan affairs, as they had done consistently during the 19th century; and if there is one consistent factor in Afghan politics, it is that they bear a long grudge.

But there was another difficulty waiting for them, along with the opium. Tony Blair had made a terrible miscalculation. If he had forgotten that the British were still more hated than any other nation in Helmand, the locals certainly hadn’t. The Battle of Maiwand had taken place nearby in 1880, which had brought to an abrupt end the last attempt the British had made to control Afghan affairs, as they had done consistently during the 19th century; and if there is one consistent factor in Afghan politics, it is that they bear a long grudge.

Ashraf Ghani, then a finance minister and now Afghanistan’s president, was quoted at the time of the British redeployment as saying that ‘if there is one country that should not be involved in southern Afghanistan, it is the United Kingdom.’ But no one had asked him, as indeed was consistent with the Allies’ blundering approach in general.

The British arrived in Helmand badly under-resourced and ill prepared for what they were about to encounter. One reason they were so stretched is that at the same time as committing to Helmand, the British Army was trying to manage an increasingly volatile situation in Basra, in Iraq. Again they had been committed by a government with a dangerous need to try and show off British military capability, even if it wasn’t there. Resources were dangerously stretched between the two missions.

Despite that, their commanders in Helmand allowed ‘mission-creep’: they found themselves establishing vulnerable control posts in wild bandit towns like Sangin and Musa Qala, where the complexities of tribal conflicts bemused them. To say they were out of their depth would be to assume they were in a swimming pool when they were in the middle of an ocean. Not that they helped themselves: they had few political officers or interpreters, so that half the time they couldn’t work out whose face was behind the beard, Taliban or friend. The situation rapidly grew out of hand, with mounting casualties.

Rather than admitting they were overextended, the British doggedly soldiered on. Due to MOD ‘accounting errors’, there were not enough helicopters to support the increasingly far-flung control posts around Helmand – and as the Taliban gained in confidence and started using road-side bombs, not enough suitable vehicles to make the increasingly dangerous journeys overland, just as in Basra. The soft-shelled Land Rovers were dubbed ‘coffins on wheels’ by the soldiers.

While initially there had not been a strong Taliban presence in Helmand, the tribes’ desire to eject the meddling British allowed them in. The Paras who were stationed there were also a blunt instrument. They might have proudly pointed out to the Americans that they had experience in counterinsurgency from Northern Ireland (perhaps not mentioning Bloody Sunday); but understanding the complexities of Northern Irish politics was a piece of cake compared to those of the Afghan tribes, and Northern Ireland was, for better or divisive worse, home soil, with the same language spoken.

Thinking about Afghanistan now, I feel an enormous sorrow for the families of the brave British soldiers killed by this rash deployment, and for those of them who survive injured or traumatised; and also an anger at the blind stupidity of the politicians like Tony Blair who sent them there.

I also feel empathy for those Afghan civilians I met who had been so trampled by the decades of conflict: the widowed women huddled in burkas in the winter streets of Kabul, begging in the mud; the orphaned children in a remote village by the Tajik frontier, fending for themselves; at the other end of the country, a child bride on the outskirts of Herat living in a hut amongst the piles of old abandoned tanks and APC’s, showing us the legs she had burned with kerosene at 12 years old as the only way she could protest at the miseries of her own existence. There been over 45,000 civilian deaths since the invasion.

I also feel empathy for those Afghan civilians I met who had been so trampled by the decades of conflict: the widowed women huddled in burkas in the winter streets of Kabul, begging in the mud; the orphaned children in a remote village by the Tajik frontier, fending for themselves; at the other end of the country, a child bride on the outskirts of Herat living in a hut amongst the piles of old abandoned tanks and APC’s, showing us the legs she had burned with kerosene at 12 years old as the only way she could protest at the miseries of her own existence. There been over 45,000 civilian deaths since the invasion.

While the US contemplates leaving completely in May, whatever anarchy may then ensue – as it surely will – have we ourselves learned anything from Afghanistan? Given that as Andrew Marr once pointed out in an interview, no British politician has ever apologised for mistakes made there.

What led us to overcommit and then suffer casualties was a wilful determination to assert a power we no longer have; and a concomitant failure to understand the country we were dealing with. The same dangerous attitude is displayed in the current Defence Review, which wants us still to be a global player: to increase our nuclear warhead capacity by 40%; to be able to intervene even though we will have fewer troops and resources to do so. There is much loose talk of ‘new technology’, just as there was when replacing the Land Rovers; but as Michael Mullen, a former head of the US military, pointed out when asked about the forthcoming British troop cuts, it’s hard to use an app when you’re in the middle of a battlefield. What matters is the practical application of force on the ground to achieve measured objectives.

If we jump feet first into another conflict again, personally I would trust Boris “let’s wing it” Johnson even less than Tony Blair. Just what are we all trying to prove, particularly when there are schools, hospitals and nurses all needing money that would otherwise be spent on warheads?

The lesson from Afghanistan is that we should not try to punch above our weight. The British Empire ended over 50 years ago. Isn’t it time we stopped trying to be one of the world’s policemen? When we could do so much better by being one of the world’s interpreters and facilitators.

———————————————–

A modified version of this piece was published by the Spectator

Further reading

Christina Lamb’s excellent two books: The Sewing Circles Of Herat and Farewell Kabul.

Sarah Chayes, The Punishment Of Virtue. Sarah Chayes spent a decade from 2001 to 2011 in the Taliban heartland of Kandahar. As I reviewed it for the Independent; ‘This passionate and engaged dispatch from the field is in the best tradition of grass-roots reporting; it is, quite simply, the best book on Afghanistan since the invasion.’

Jack Fairweather, The Good War. Fairweather is a fine writer whose later The Volunteer rightly won the Costa Book Of The Year Award – this is one of the best, most straightforward accounts of the conflict up to 2014. A Million Bullets by James Ferguson is another, earlier one.

William Dalrymple, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, a brilliantly written account of the first 19th century British campaign in Afghanistan and its dramatic failure. What a shame it was only published in 2013, just as the British were leaving Afghanistan this time around, as it might have helped focus minds before they arrived.

James Meek, ‘Worse than a Defeat’, LRB : Wide-ranging review which covers Jack Fairweather’s book above, but extends wider.

Excellent overview of the fatal decision not to negotiate with the Taliban after the invasion in the first place by Max Fisher in the New York Times .

Both Restrepo and the follow-up film, Korengal, follow the fortunes of an American platoon in a remote valley in eastern Afghanistan, and give a gritty sense of fighting within a community where you don’t know who is your enemy. Available on various streaming platforms like Amazon Prime and Netflix. And a welcome antidote to the terrible feature film Lone Survivor which should be avoided at all cost.

Andrew Mackay’s ‘Afghanistan’s: The Lessons of War’, broadcast on BBC R4. As a former major general in Afghanistan, Andrew Mackay gives an interesting analysis which, while diplomatic as one might expect, also clearly recognises the problems the British Army encountered there.

And for completists, nothing beats reading the sobering House of Commons Review of the Afghan campaign. Like: ‘We subsequently asked other Ministry of Defence (MoD) witnesses on 10 November 2010 about the deployment to Helmand in 2006 including the size of the deployment and the intelligence on which it was based. The answers we received were far from satisfactory: we were left with the impression that the MoD intended to minimise what we were told about how decisions were made to deploy to Helmand in 2006 and then to expand the deployment.’